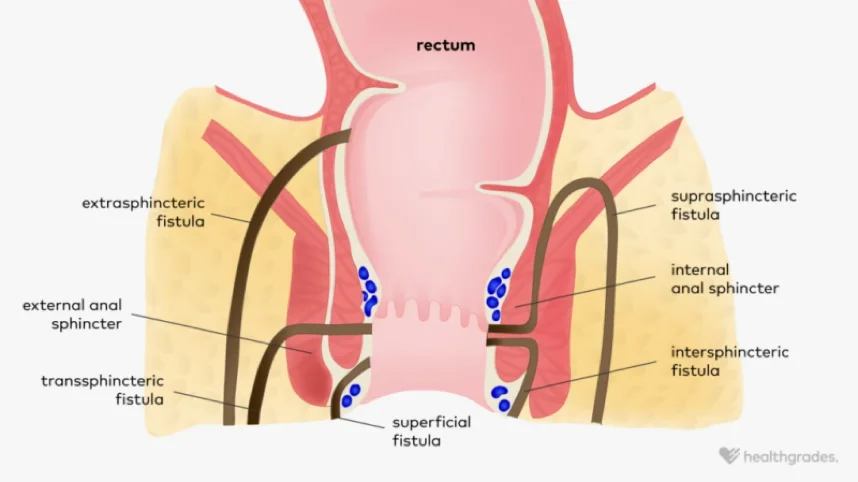

A definition: A fistula is the communication between two epithelialised surfaces. An anal fistula is a communication, or tunnel, between the lining of the anal canal and the external skin of the buttocks or perianal region.

A little bit of anatomy, physiology and pathology: The anal canal is the last 3-5 cm of the intestinal tract. It is surrounded by 2 circular muscles, called sphincters, which help to defer our need to defaecate (empty) until an appropriate time and place – ie the toilet!

The upper half of the anal canal is lined by mucosa which makes mucous, but the lower half is dry skin. We have 12 anal glands within the anal canal around where the mucosa merges with the skin. It is thought these glands may help lubricate the passage of poo.

Most mammals have anal glands. In humans, a gland can become blocked and then infected. Often, there is no cause for this. It’s like a blocked skin pore leading to a pimple or a boil. Once blocked and infected, bacteria continue to grow and cause a build-up of pus.

Pus and bacteria act like acid and cause further tissue death leading to an expanding abscess. These are literally a pain in the butt! An abscess needs to be drained surgically. It can spontaneously discharge if the afflicted person can put up with severe pain until this occurs.

The internal opening can then become unblocked and a fistula arises.

Once a fistula occurs, there is an ongoing discharge from the buttock / perianal wound. The inner opening of the fistula lies within the anal canal which can be considered a ‘high pressure’ area. The outer opening is in a lower pressure area, and bacteria (and occasionally faeces) are pushed through the tunnel to this external opening.

The skin tries to heal. In some people the skin does heal and subsequently a recurrent abscess occurs. A cycle of recurring pain, followed by discharge, can arise.

Treatment: A fistula is very unlikely to heal without surgical management. Antibiotics can decrease the amount of swelling and discharge, but once the course is completed, the fistula symptoms recur. Virtually any fistula will heal if it’s cut out or layed open.

The problem is that the fistula tunnel often travels through the sphincter muscles and can be difficult to identify throughout its length. It may have multiple tracts. Laying open the fistula involves division of some muscle. If too much muscle is cut, the wound may heal but the patient can become incontinent.

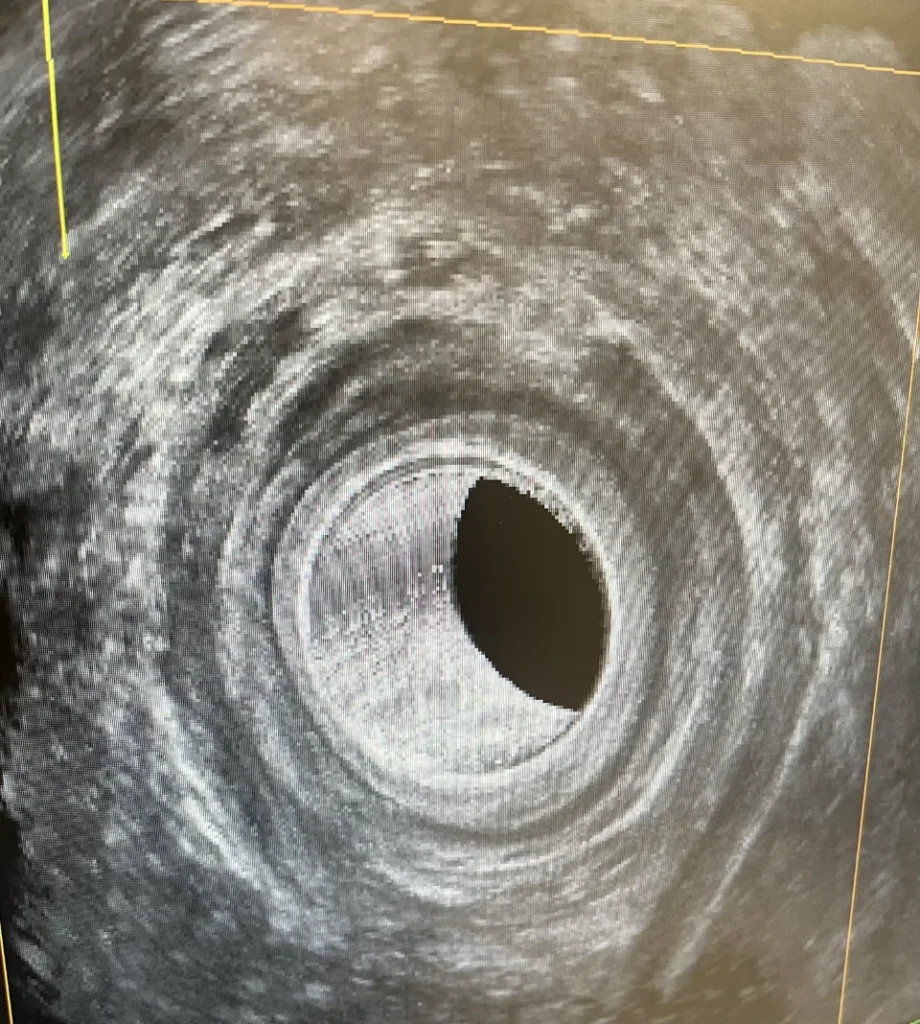

While there are other methods to treat an anal fistula that don’t involve cutting any sphincter muscle, but these have much lower success rates. An anal ultrasound, especially one with a 3D reconstruction, gives the surgeon a 3 dimensional roadmap to help plan surgery. It helps identify the internal opening and if secondary tracts have arisen.

The ultrasound shows the surgeon the anatomy of where the tracts are and how much sphincter muscle is involved. Importantly, it also shows how much muscle will be left if the tract is suitable to be layed open.

An 3D ultrasound image demonstrating a right sided fistula arising from the midline of the posterior canal.